What’s the best way to teach business?

In recent years, schools have started to move toward more experiential learning, a deeper focus on softer skills, and multidisciplinary curricula. While traditional classroom styles and subjects still persist, new perspectives are slowly changing the way business students worldwide learn about industry and commerce. In the next few pages, two unconventional educators advocate for fresh approaches to the business school classroom as they call for teaching methods that are anything but traditional.

Education and the Curious Child

I once saw this phrase on a T-shirt: “We were all creative till education happened to us.” That indictment of the modern educational system echoes an observation made by Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore back in 1929, when he described education as an institution that “had its luggage van waiting for branded bales of marketable result.”

It’s time for a change.

I believe that educators must approach learning as an activity that happens every day, around the clock; I believe that their goal must be, not to disseminate knowledge, but to inspire their students with a thirst for knowledge. Each session should end with students racing out of the classroom to learn more about the day’s topic through their own experiments.

I think our students would benefit immensely if business schools took Tagore’s viewpoint to heart. Tagore, an outspoken critic of the rote lecture style of education, emphasized that teachers should see the world as a global village populated by curious children eager to fill their empty minds not just with data, but also with wisdom and experiences and the conviction that curiosity pays rich dividends. He recommends two simple yet effective teaching methods: teaching through experimentation, which takes students out of the classroom so they can get firsthand experiences; and active learning, in which educators perform fewer monologues and students engage in more discussions and debates.

Teachers should see the world as a global village populated by curious children eager to gain wisdom and experience

How We Learn

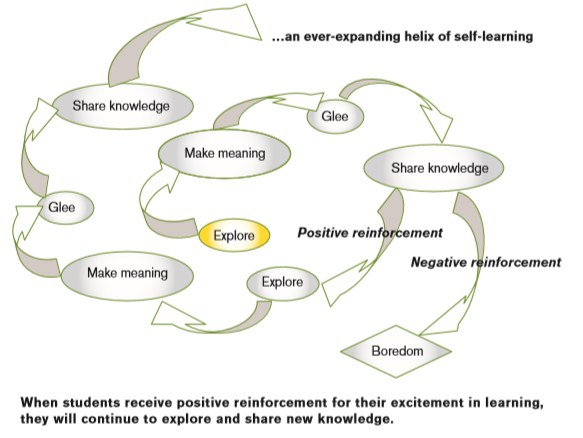

If we are going to encourage our students to truly learn, we first must understand how learning happens. Mitchel Resnick of MIT’s Media Lab has described the learning experience as the “imaginecreate-play-share-reflect-imaginecreate” cycle.

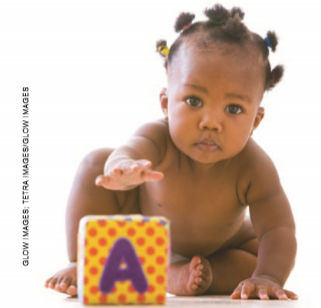

It might be easier to understand if you visualize what happens when you hand a new toy to an 18-month-old toddler. She looks at it from all angles, shakes it, holds it to her ear, bites it, throws it on the floor, digs into it with her fingers, squeezes it, sniffs it. This is curiosity at its best. The child is using all five senses—sight, sound, touch, smell, and taste—to explore the new thing she’s been given.

When one of her experiments leads to an outcome—the toy makes a sound—she repeats a few of her actions until she can isolate cause and effect. When she learns that squeezing the toy causes it to squeak, she experiences a Eureka! moment of unbounded glee. She prances around, repeating the act, thrilled anew every time the toy reproduces the desired outcome. When she sees the adult watching, she rushes over to show what the toy can do. In effect, she is sharing the knowledge pool she has created out of her own explorations.

The adult pretends to be awestruck, and this positive reinforcement encourages the child to go back to the toy for the next round of exploration, attempting to make some other meaning out of the same object. Perhaps she finds that it squirts water out when she squeezes it, and she quickly shows that ability to the adult audience as well. She has gotten into an ever-expanding helix of exploring, making meaning, experiencing glee, and sharing.

The adult audience plays a key role in her learning cycle. If, instead of participating approvingly in her triumph, the adult says, “The toy is not supposed to make noise,” he kills the child’s sense of accomplishment.

This is exactly what our educational system does when it creates an environment where teachers are always right and their views are the only possible interpretations of events. Creative children might answer test questions with their own unique interpretations, but they are likely to receive zero points for the exam or be admonished for fantasizing in class. These repeated snubs cause them to lose interest in the subjects they’re studying; they eventually stop learning and begin “aping” what they’re told in class or read in books.

This mimicry is not a path to learning. And it’s definitely not a path to the innovation the world requires if we are to solve tomorrow’s problems.

A New Approach

I believe business school education must produce graduates who are open-minded and flexible enough to grasp the changes occurring in the world, dip into their knowledge pools, connect the dots across different disciplines, and generate synergistic solutions. If schools want to develop students with creative minds, they need to develop an approach in which individuals:

- Are unafraid of starting from a blank canvas.

- Can see linkages and apply fundamental concepts across seemingly unrelated fields.

- Are willing to experiment continuously and act on the feedback received.

- Can visualize possible scenarios and view the larger picture without the interference of functional silos.

- Can appreciate the needs of various stakeholders. !

- Can see models end-to-end, whether they’re about consumer experiences or business initiatives.

This approach to problem solving is known as design thinking, which is already being taught at a few business schools (see “Design Think at Innovation U” in the November/December 2007 issue of BizEd and “Management Meets Design” in the September/October 2010 issue). Students who learn this iterative, collaborative way of thinking learn to reframe problems and come up with better and more integrated solutions.

Design Thinking in the Classroom

At the Welingkar Institute of Management Development & Research, we teach this way of thinking in our PGDM Business Design & Innovation (post-graduate diploma in management) program. We have structured the course so we deliberately keep students away from functional specializations in marketing, finance, operations, HR, and other conventional MBA disciplines. Instead, we rely on a multidisciplinary approach that encourages them to experiment and learn through the “imagine-create-playshare-reflect-imagine-create” cycle. In fact, we take students through the entire business cycle, from creation to exit, in four key steps:

1. Identifying needs and spotting opportunities. We send students out to do firsthand research in various sectors—such as telecom, banking, insurance, and IT—and to explore the pain points and aspirations of consumers. At the same time, to support students in the discovery process, we teach subjects such as research methodology, ethnography, individuals and society, and applied economics.

We also give students a practical introduction to the basics of marketing, finance, and operations by assigning them to a company to study its operations. Through this module, students acquire a groundlevel understanding of what consumers want and how business works in reality.

2. Generating concepts. After identifying opportunities in various markets, students pick a sector where they can generate viable business concepts. First they go through a systematic, in-depth, milestone-based sector analysis. Then they study other subjects— including market research, environmental issues, interactive design, accounting, and so on—so they can create viable concepts based on the realities of the sectors they choose.

3. Planning for rollout. Students learn everything they need to launch a business: developing a business plan, prototyping, branding, financing, project management, strategic marketing, corporate law and taxation, and operations research. This section also includes a week called “Exploring the Grass Roots,” during which students visit rural India to research various aspects of village life. They explore communications and banking systems, the healthcare infrastructure, and energy consumption patterns in rural India. These visits make them consider how they can grow their businesses in ways that will be sustainable and also improve village life.

4. Taking the concept to market. In this final module, students create plans for financing, marketing, operating, staffing, and mitigating the risks for their chosen enterprises. They attain the necessary know-how through subjects like innovation management, international business, integrated communication management, advanced prototyping, quality management, and advanced financial management. The module ends with a forum where they display their ideas to a panel of industry experts. Angel investors and venture capitalists also attend, so there is potential for the most promising ideas to receive funding.

Feedback for the Future

Students have responded enthusiastically to this business design and innovation program. According to 2008 student Sunny Gandhi, the course “made me open to new ideas and thoughts without judging their impact beforehand.” Sweety Jain, a student from 2011, said that the class “led to the transformation of my thinking from ‘how’ to ‘why’ and ‘what,’ and from there to a customized approach to solving the pain points of the consumer.”

Even more tellingly, 2012 student Sweta Nair commented that the business design course “has been like a reincarnation experience. It taught me to be detached from my own creation, to allow ideas and concepts to evolve and adapt with time and changing requirements. I have learnt that everything in nature is a cycle and hence to consciously plan for the end as we do for its creation.”

I am convinced that the model of business education for the future must move away from a one-way dissemination of facts and figures. It must encourage students to explore, connect the dots, form their own constructs, test them, reconstruct them, and refine them. Only then will graduates defy today’s “dominant logic,” as C.K. Prahalad referred to cultural norms and beliefs. Only then will they move beyond “functional fixedness,” which Karl Duncker defined as a “mental block against using an object in a new way that is required to solve a problem.” Only then can students be industry-ready—and only then can we say that our universities are doing their jobs well.